Case report Orient Mitaka Clinic

Summary

Two patients with disseminated testicular tumors (seminoma with/without other histologies) were treated by chemotherapy following orchiectomy. The tumor masses regressed with chemotherapy and a partial response (PR) was achieved in both patients. One patient refused further chemotherapy because of side effects and the other was unable to receive further chemotherapy because of interstitial pneumonia. Therefore, they presented to our clinic for treatment with biological response modifiers consisting of fungal mycelium extracts¹) instead of receiving further conventional chemotherapy. One patient had recurrence of seminoma with metastasis to the retroperitonium, and the other had metastatic lesions in the lungs and abdominal aortic lymph nodes. Those metastases became undetectable on CT scans at 1.3 years and 8.9 years, respectively, after the initiation of treatment with fungal extracts following their previous chemotherapy. They both tolerated treatment with the fungal extracts. Both patients are now ( October, 2010) leading a healthy and uneventful life at 9 years and 5 years after achieving a complete response, respectively.

Interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and interleukin-12 (IL-12) production²) by stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were measured in order to monitor the immune status of the patients during treatment with fungal extracts. Data obtained by monitoring of the tumor dimensions, tumor markers, and IFN-γ and IL-12 production showed that tumor regression was significantly associated with each patient’s immune status (IFN-γ and IL-12 titers). Therefore, it is concluded that the immune status of cancer patients is a useful prognostic factor for the response to treatment, and that administration of fungal extracts appears to be effective and beneficial for patients with disseminated testicular tumors.

Case report

Swelling of the left testis was reported in 1986 when the patient was 31 years old. The tumor was resected by high orchiectomy, and was histologically diagnosed as a pure seminoma that was clinical Stage I (T1 N0 M0). Surgery was apparently curative and the patient was followed without adjuvant radiation therapy or chemotherapy for 12 years postoperatively. During this long period, there was no sign of recurrence at regular annual reviews. In 1998, the patient reported some nonspecific symptoms and elevation of serum LDH to 1,312 U/l was detected. In March 1999, CT scanning revealed a retroperitoneal mass that measured 159.515 cm

(Fig. 1a). The mass was mainly located on the left side of the abdominal aorta and extended from the left renal hilum to the aortic bifurcation. The left ureter was involved, resulting in left hydronephrosis. No other metastases were detected.

CT-guided needle biopsy confirmed the presence of viable malignant cells, which were histologically compatible with seminoma. The serumHCG-β level was 2.4 ng/ml, serum neuron-specific enolase was 42.3 ng/ml, and LDH was 1,005 IU/l. Accordingly, a diagnosis of metastasis of seminoma to the retroperitoneal region was established. The tumor was subsequently found to involve the abdominal aorta, inferior vena cava, hepatic vessels, right and left renal vessels, and inferior mesenteric artery from the results of CT, MRI, and ultrasonography. Therefore, the tumor was judged unresectable, and the patient received chemotherapy instead.

Combination chemotherapy consisted of cisplatin (100 mg/m2) on day 1, etoposide (100 mg/m2) from day 1 to day 5 consecutively, and bleomycin (30 mg/body) on days 1, 8, and 15, followed by a week of rest before the next course. Four courses were planned for administration. Two days after starting the first course in March 1999, the palpable abdominal mass was reduced in size. The patient subsequently experienced mild reversible renal dysfunction and ileus that led to transient small bowel obstruction. The second course of therapy resulted in reduction of the tumor size to 7×4.5×8 cm on CT scans (

Fig. 1b). The serumHCG-β level decreased to the normal range (<0.1 ng/ml) by the first day of the second course (March 29). During the third course of therapy, severe anemia necessitated blood transfusion and the patient also developed severe nausea and vomiting. The fourth course was started on May 9. Administration of bleomycin caused high fever (39.3C) associated with intractable nausea and vomiting, leading to the discontinuation of bleomycin. The WBC count decreased to 500 cells/ml, requiring the administration of colony-stimulating factor. Thrombocytopenia also occurred and he underwent platelet transfusion three times (May 21, 22, and 25). The fourth course was completed on June 4, 1999. The tumor remained around the same size (8 cm in diameter) as had been observed on CT scans during the second course in April (

Fig. 1c). Thus, the response to chemotherapy was evaluated as a partial response (PR) because of the substantial residual tumor mass. A new chemotherapy protocol with peripheral blood stem cell transfusion was suggested, but he refused further chemotherapy because of possible serious side effects. Instead, the patient opted for treatment with biological response modifiers, including fungal mycelium extract.

Patient N.T. was aged 31 years old when a right testicular tumor was diagnosed in September 1995. He had multiple metastases to the lungs, abdominal aortic lymph nodes, and a mandibular lymph node, so the disease was diagnosed as Stage IIIC. The serum HCG level was over 9,000 mIU/ml. The patient underwent high orchiectomy on September 26. The tumor measured 2.5 cm in diameter and showed a mixed histological picture, comprising anaplastic seminoma, embryonal carcinoma, yolk sac tumor, choriocarcinoma, and mature teratoma. Combination chemotherapy with cisplatin, etoposide, and ifosfamide was initiated immediately after surgery. A total of 5 courses of treatment were given until February 24, 1996 (cisplatinum and etoposide on September 30, 1995, as well as cisplatinum, ifosfamide, and etoposide on October 14, November 4, November 25, and December 16, 1995, and January 31, 1996). Bleomycin was added to cisplatinum and etoposide on January 12 and February 24, 1996.

After completion of 5 courses, the metastasis to the mandibular lymph node disappeared. The serum HCG andHCG-β levels decreased to 2.3 mIU/ml (normal<1.0 mIU/ml) and 1.1 ng/ml (normal<0.2 ng/ml), respectively. He developed dyspnea due to interstitial pneumonia or pulmonary fibrosis and peripheral neuropathy twice after doses of bleomycin, and did not tolerate the chemotherapy well. Therefore, chemotherapy could not be continued and the patient requested alternative treatment with biological response modifiers (fungal mycelium extract). Although chemotherapy had resulted in disappearance of one of the three major metastases (the mandibular lymph node metastasis) on CT scans (not shown), the other two major sites of metastasis (multiple lung lesions and enlarged abdominal aortic lymph nodes) were still present.

Clinical Course During Treatment With Fungal Extracts

1. Changes of tumor size and tumor markers

The patient was orally given IL-X (a hot water extract of Lentinus edodes and Ganoderma lucium) at a dose of 6 g daily and Krestin (Coriolus versicolor) at a dose of 3 g every other day. Treatment with these fungal mycelium extracts was started on September 16, 1999. The retroperitoneal tumor had a diameter of 8 cm on CT scans at the start of treatment (September 16, 1999) (not shown) and was the same size as 3 months earlier when chemotherapy had been discontinued. The tumor decreased to 4 cm in diameter on April 10, 2000, as shown in Fig. 1d and was the same size on August 15, 2000 (not shown). Thereafter, it showed a change to scar tissue containing calcification without viable tumor tissue on CT scans obtained on January 23, 2001 (

Fig. 1e). As the tumor-like lesion was virtually undetectable on CT, Krestin was discontinued on March 6, 2001 and the dose of IL-X was reduced from 6 g/day to 2 g/day. There have been no significant changes of imaging findings from that time up to October 2009 (

Fig. 1f), suggesting complete disappearance of the tumor. Therefore, the response was assessed as a complete response (CR).

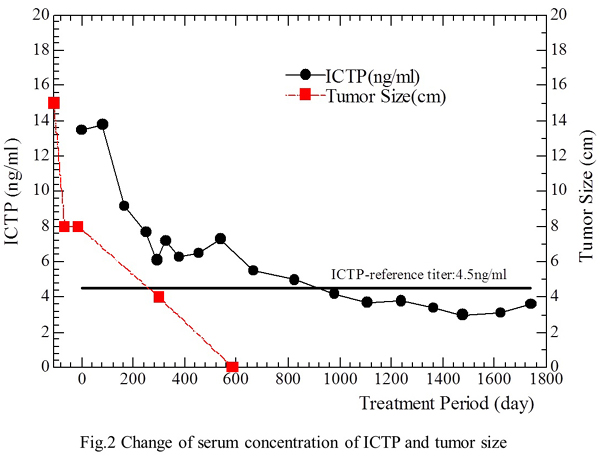

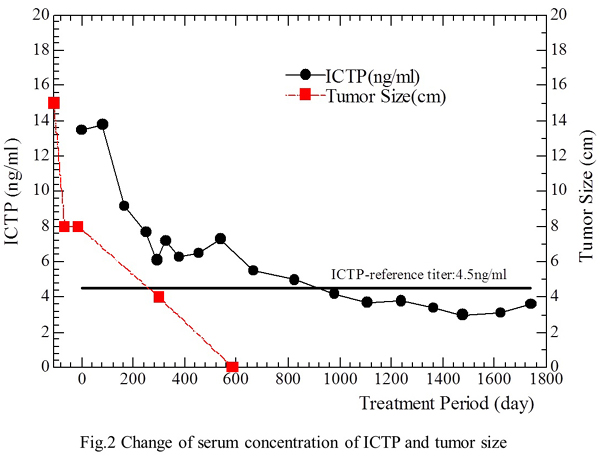

Regarding tumor markers, both HCG andHCG-β were in the normal range on September 16, 1999 (start of treatment), while serum type 1 collagen C-telopeptide (1CTP), a marker of bone metastasis or osteoporosis, was above the normal range at 13.5 ng/ml (normal<4.5 ng/ml) when treatment started. However, the patient had no evidence of bone metastasis or osteoporosis on bone scintigraphy. Despite this, 1CTP remained abnormal at 6.6 ng/ml on January 24, 2001 when the tumor was not detectable on CT. The 1CTP value eventually returned to the normal range (4.2 ng/ml) on May 21, 2002, at 2.8 years after the start of treatment and no abnormalities of 1CTP have been observed since. The patient tolerated treatment well without any side effects throughout therapy. The correlations of treatment with the changes of tumor size and 1CTP levels are shown in the Fig. 2.

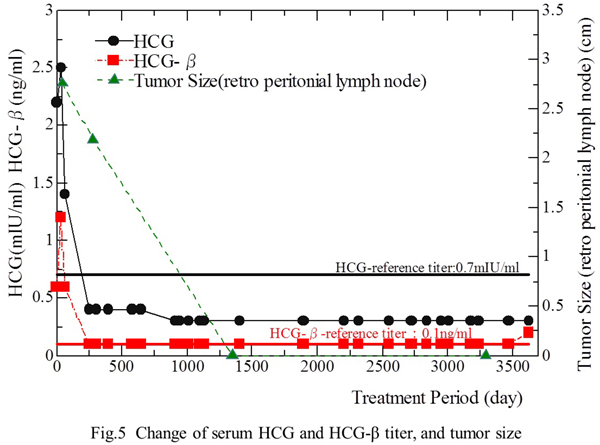

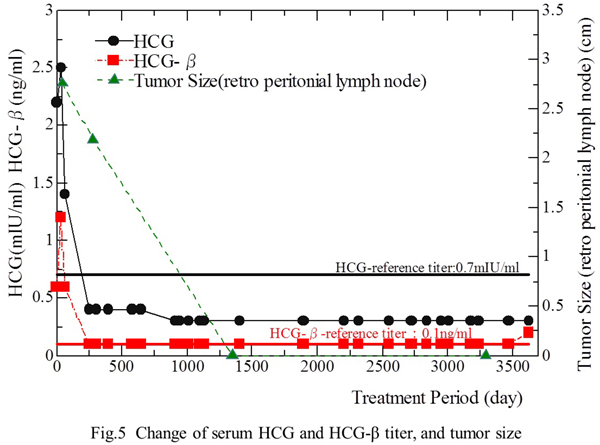

IL-X treatment was started on June 12, 1996, at three months after the discontinuation of chemotherapy. IL-X was given orally at a dose of 3 g daily from June 12, 1996 to July 12, 2002. Then the dose was reduced to 2 g/day and treatment was continued up to October 2007. At the start of treatment, the patient had multiple metastases in the lungs and abdominal aortic lymph nodes on CT scans. The pulmonary metastases were too numerous to count, but there were 3 major lesions (

Fig. 3a), while the abdominal aortic lymph node metastasis measured 2.8 cm (

Fig. 4a). After treatment was started, some of the lung metastases regressed and there were fewer pulmonary metastatic lesions on CT scans obtained on January 31, 1997 (

Fig. 3b-1, Fig. 3b-2). The abdominal aortic lymph nodes decreased in size by 70% on CT (February 3, 1997) (

Fig. 4b). Serum HCG andHCG-β levels also decreased below 0.4 mIU/ml and 0.1 ng/ml, respectively (i.e., the normal range). The patient was able to return to daily activities in July 1997. At 3.6 years after the start of treatment (January 7, 2000), the three distinct metastases in the lungs showed marked regression on CT (

Fig. 3c), and the abdominal aortic lymph nodes also showed a decrease in size (

Fig. 4c), but small metastases were still scattered through the lungs (

Fig. 3c). The tumor masses showed a significant decrease in size on January 7, 2000 and the dose of IL-X was reduced from 3 g/day to 2 g/day on January 12, 2000. At 9 years after the start of treatment (May 7, 2005), all of the metastases in the lungs and abdominal aortic lymph nodes became undetectable by CT (

Figs. 3d-1, Fig. 3d-2 and 4d). No marked changes of imaging findings have been observed since then up to September 2, 2009 (

Fig. 3e-1, Fig. 3e-2, and Fig. 4e). The response to treatment was therefore assessed as a complete response (CR).

The relationship between treatment and the changes of the tumors is indicated in Fig. 5.

2. Immunological monitoring

The status of cell-mediated immunity in the two patients was assessed during treatment with the fungal extracts by measuring IFN-γ and IL-2 production by stimulated PBMCs.

1) Changes of IFN-γ in relation to tumor size and tumor markers during treatment with fungal extracts

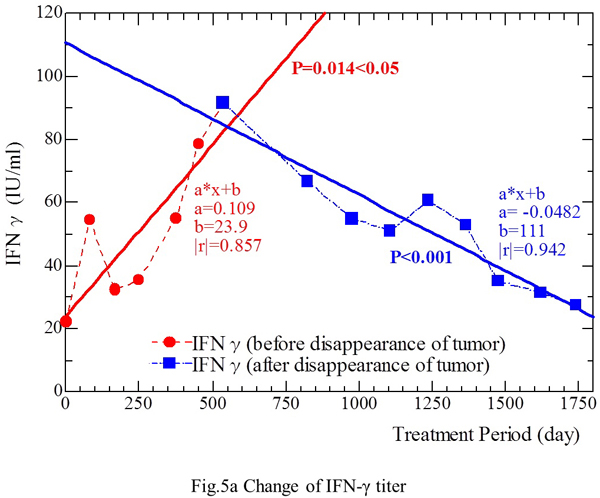

a) Patient M.F.

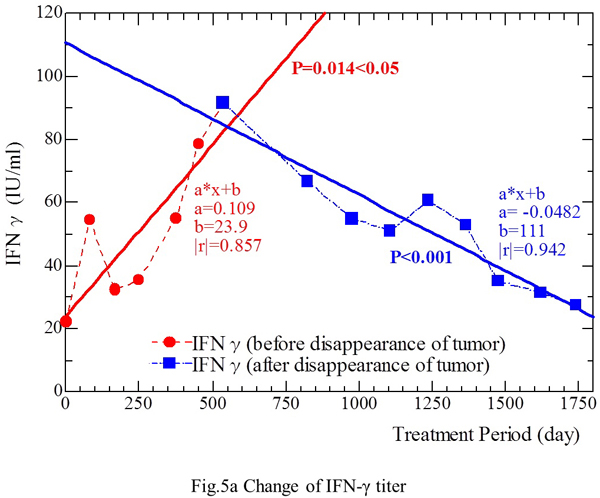

Combined treatment with IL-X and Krestin was started on September 16, 1999. Thereafter, the IFN-γ level increased from 22.4 IU/ml (September 16, 1999) to 91.6 IU/ml (March 6, 2001), which was the peak level throughout the observation period (Fig. 5a). The tumor decreased in size from 8 cm (September 16, 1999) to scar-like tissue (January 23, 2001) on CT. However, the level of 1CTP, a tumor marker, remained in the abnormal range at 7.3 ng/ml (normal<4.5 ng/ml). On March 6, 2001, Krestin was discontinued because the tumor had decreased to residual scar tissue on CT scans. Administration of IL-X was continued because of the potential for microscopic tumor to remain. Three months later (June 5, 2001), the dose of IL-X was reduced from 6 g/day to 2 g/day since the patient was in a stable state and appeared to have no active tumors.

As shown in Fig. 5a, the IFN-γ level decreased from 91.6 IU/ml (March 6, 2001) to 27.6 IU/ml (June 21, 2004), except for slightly high titers of 60.8 IU/ml and 53.0 IU/ml on February 4, 2002 and June 10, 2003, respectively (Fig. 5a). The IFN-γ level (IU/ml) showed a linear correlation with the period of treatment with fungal extracts (Fig. 5a) [Y (IFN-γ level) = 0.109 X (treatment period) + 23.9] from September 16, 1999 to December 12, 2000 (Pearson’s coefficient |r|=0.857, p<0.05). This relation was also confirmed [Y = -0.0482 X + 111 (|r|=0.942, p<0.001)] in the period from March 6, 2001 to June 21, 2004, when there was no evidence of tumor on CT scans. Thus, the IFN-γ level fluctuated throughout the period of fungal extract treatment, increased along with the reduction of tumor size, and decreased after disappearance of the tumor.

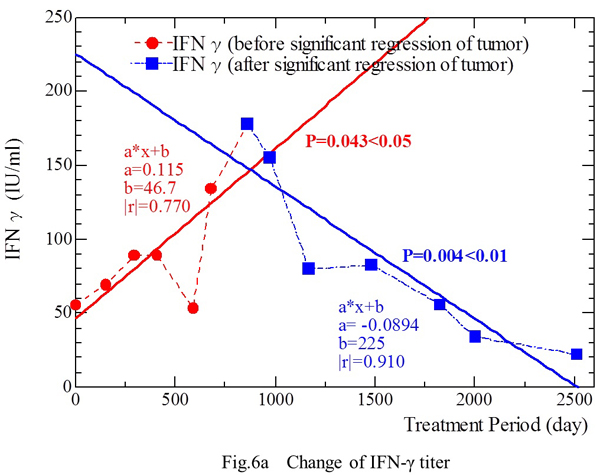

b) Patient N.T.

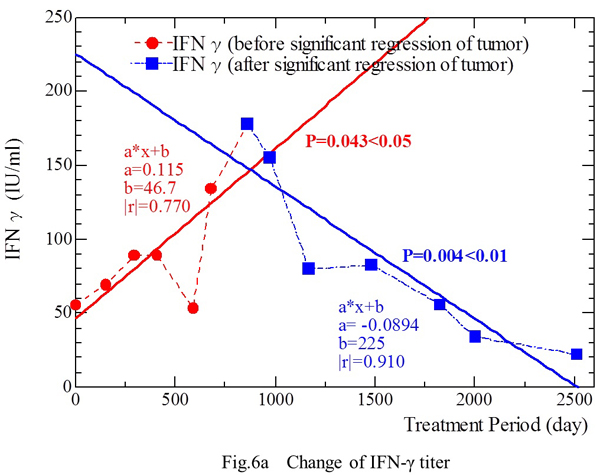

Administration of IL-X was started at a dose of 3 g/day on June 12, 1996. Measurement of IFN-γ was possible from April 23, 1998. The IFN-γ level was 55.8 IU/ml on day 1, and it increased to 134 IU/ml (March 3, 2000) and then to a maximum of 178 IU/ml on September 1, 2000 (Fig. 6a), after which the two metastatic lesions decreased markedly in size (Figs. 3c and 4c). The IFN-γ level started to decrease from September 1, 2001, and was 22.3 IU/ml on March 12, 2005 (Fig. 6a), just before all metastatic lesions disappeared on CT scans on May 7, 2005 (Figs. 3d and 4d). The dose of IL-X was reduced from 3 g/day to 2 g/day on July 12, 2002, as the metastases decreased in size (Figs. 3c and 4c). The IFN-γ level (Y-axis: IU/ml) showed a linear correlation with the period of treatment with fungal extracts (X-axis: days) (Fig. 5a) [Y = 0.115 X + 46.7 (|r|=0.770, p‹0.05)] from April 23, 1998 to March 3, 2000, and also showed a correlation [Y = -0.0894 X + 225 (|r|=0.910, p‹0.01)] from September 1, 2000 to March 12, 2005 (Fig. 6a).

Therefore, a similar correlation between tumor mass and changes of IFN-γ was observed in both patients during the period when the tumor showed diminution or significant reduction, i.e., IFN-γ production by stimulated PBMCs probably decreased secondary to the reduction of tumor size.

2) Changes of IL-12 in relation to tumor size and tumor markers during treatment with fungal extracts

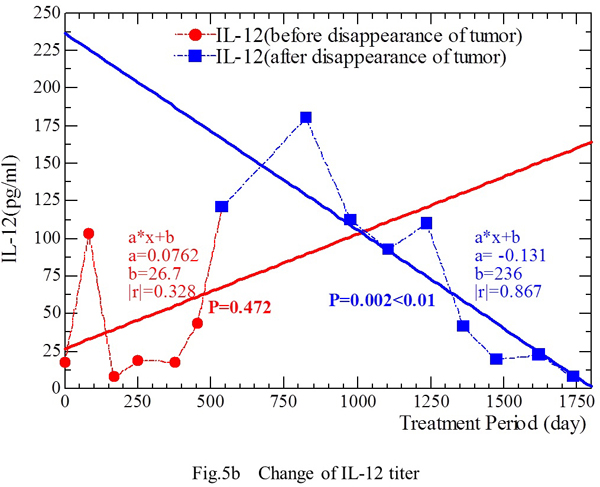

a) Patient M.F.

The IL-12 level showed the following changes during treatment (Fig. 5b). From September 16, 1999 to December 12, 2000, the IL-12 level (Y) increased as the duration of treatment (X) was prolonged [Y = 0.0762 X + 26.7(|r|=0.328, p=0.472)]. From March 6, 2001 to June 21, 2004, when no tumor was detected on CT, the IL-12 level (Y) was correlated with the duration of treatment (X) [Y = -0.131 X + 236 (|r|=0.869, p<0.01)] (Fig. 5b). The IL-12 level was positively correlated with the treatment period (i.e., it increased) as the tumor showed regression, but it was negatively correlated with the treatment period (i.e., it decreased) after disappearance of the tumor on CT and these associations showed statistical significance.

The level of 1CTP, a marker of bone metastasis, was abnormally high (>4.5 ng/ml) until May 20, 2002, which was 1.4 years after the tumor became undetectable on CT. 1CTP returned to normal on September 26, 2002.

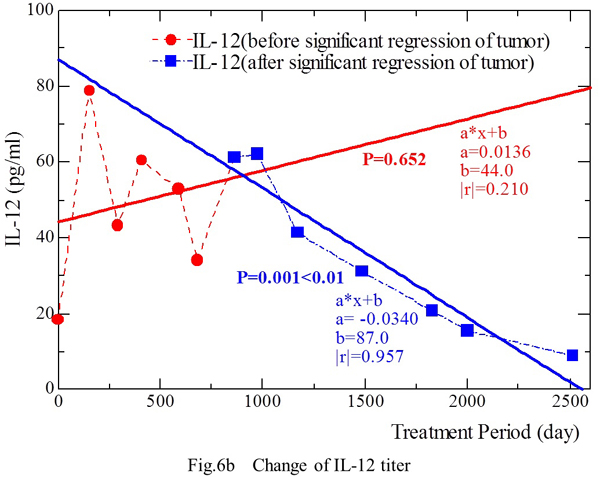

b) Patient N.T.

The IL-12 level (Y) showed an increase along with prolongation of the treatment period (X) from April 23, 1998 to March 3, 2000 [Y = 0.0136 X + 44.0 (|r|=0.210, p=0.652)] (Fig. 6b). During this period, the tumor masses in the lungs and abdominal aortic lymph nodes showed significant regression on January 7, 2000. During the period from September 1, 2000 to March 12, 2005, the masses were disappearing on CT and the IL-12 level (Y) decreased along with prolongation of the treatment period (X) [Y = 0.0340 X + 87.0 (|r|=0.957, p‹0.01)].

This phenomenon was observed in both patients, suggesting that IL-12 production by stimulated PBMCs decreased in the period after significant regression or disappearance of tumor masses.

Discussion

Two patients with testicular tumor are reported here, one with metastatic seminoma that recurred 13 years after curative surgery and the other who had an advanced testicular tumor of mixed histology with multiple metastases to the lungs and the abdominal aortic lymph nodes. Both were treated with BRMs containing fungal mycelium extracts following chemotherapy alone in the former patient and the combination of surgery plus chemotherapy in the latter. The former patient with metastatic seminoma refused further chemotherapy because of serious side effects, and the other was unable to continue chemotherapy because of interstitial pneumonia. These patients had responded to chemotherapy (PR), but large tumor masses still persisted in both cases. Treatment with BRMs containing fungal extracts for 1.3 and 8.9 years, respectively, abolished all the lesions on CT scans and X-ray films in the two patients.

Burn-out of testicular tumors or spontaneous regression has been reported histologically and clinically, but is considered to be very rare event. The “burned-out” phenomenon refers to spontaneous regression of a “primary” testicular tumor that usually presents with extragonadal meatastasis, most often with tumor remnants in the testis. Spontaneous regression of extragonadal metastases has also been reported anecdotally in patients with both seminomatous and nonseminomatous germ cell tumors. It is hard to conclude which of the two types shows more frequent spontaneous regression3).

True spontaneous regression of distant metastases arising from testicular cancer is an event of extreme rarity and only 20 such cases have been reported so far4). Most of the testicular tumors for which regression was reported were nonseminomatous tumors (most commonly embryonal carcinoma and teratocarcinoma), so regression of metastatic seminoma is even more uncommon5).

Spontaneous regression has been reported in virtually all types of human cancer, and a total of 176 cases of spontaneous regression were found by searching the literature over the past 70 years. The phenomenon is extremely rare (around one in 100,000 cancer patients). More than half of the cases are accounted for by carcinoma of the kidney (17.6%), neuroblastoma (16.5%), malignant melanoma (10.8%), and choriocarcinoma (10.8%)6). The mechanisms proposed for spontaneous regression of cancer include the host immune response, tumor inhibition by growth factors and/or cytokines, induction of differentiation, hormonal factors, elimination of carcinogens, tumor necrosis and/or inhibition of angiogenesis, psychologic factors, apoptosis, and epigenetic mechanisms7). No single mechanism can satisfactorily explain these phenomena for any type of tumor, although indirect evidence points to a possible role for host immunity8). Some compelling evidence for immune-mediated spontaneous regression of cancer has been shown histologically, including massive cytotoxic T cell infiltration with mature dendritic cells as well as significant upregulation of MHC expression9).

Spontaneous regression is usually defined as complete or partial disappearance of a cancer that cannot be attributed to treatment, if any has been given. Regression of the massive metastases in our two cases may possibly be considered as spontaneous, but we consider that the therapeutic role of BRM treatment was important. One of our patients (MF) may be the first reported in whom a large metastatic tumor developed 13 years after curative orchiectomy for pure seminoma and 4 courses of chemotherapy did not eliminate the bulky retroperitoneal mass, although it subsequently disappeared after treatment for 16 months with BRMs including fungal extracts. The second patient (NT) was also a rare case because all of the metastatic lesions in the lungs and abdominal aortic lymph nodes from a mixed cellularity testicular tumor persisted despite 5 courses of chemotherapy, but subsequently disappeared after treatment with fungal extracts for 8.9 years. Therefore, the mode of regression seen in these patients appears to be different from that categorized as “spontaneous” regression or the burned-out phenomena. Large tumor masses still remained after the cessation of chemotherapy in both cases and the bulky masses did not show any regression during the period without intervention (e.g., in patient MF the abdominal tumor was 8 cm in size at the end of chemotherapy and remained the same size for 2 months), but regressed gradually during treatment with BRMs including fungal extracts.

Some cancers appear to have an unpredictable natural history and spontaneous remission suggests that the host immune response might have been activated10). In the clinical setting, sequential histological examination of the infiltration of immune cells and MHC expression around tumors is not easy, so we employed measurements of IFN-γ and IL-12 (produced by stimulated PBMCs) to monitor the host immune status and assess the correlation between host immune status and tumor activity during treatment with fungal mycelium extracts. We also monitored the tumors by imaging studies (CT and X-ray films) and by tumor markers.

The levels of IFN-γ and IL-12 showed significant changes over time, being higher when the tumor masses were larger and decreasing significantly after involution or significant regression of the tumors. This characteristic association between immunological status (the levels of IFN-γ and IL-12) and the tumor masses was persistently observed throughout the course of these two patients. Because induction of the secretion of these cytokines may reflect the immunological status, we used PHA for stimulation of PBMC. Although the tumor cells of a patient might be considered an ideal and more appropriate stimulator, we were unable to obtain tumor tissues or establish tumor cell lines from the tissues. Based on the present results, it seems that nonspecific stimulants such as PHA could be applicable for monitoring the immune status of cancer patient by assessing IFN-γ or IL-12 production. The level of IFN-γ and IL-12 production by stimulated PBMC may provide prognostic information for patients with tumors such as testicular cancer.

Tumor heterogeneity, variation in the expression of tumor-associated antigens, and suppressive mechanisms that may be activated to prevent the immune response from being effective must be considered in order to understand the potential of tumor defense mechanisms to completely block the immune response against cancer, as well as to interpret the clinical response to immunotherapy. Therefore, the complex host/tumor interaction may ultimately determine the therapeutic efficacy of any treatment. Accordingly, when considering the effectiveness of fungal extracts in our patients with testicular tumors, these extracts appear to play an important role in fighting against cancer through enhancement of host immune mechanisms, so obtaining a better understanding of their influence on the immune response to cancer in the clinical setting is undoubtedly important.

Legends

Fig. 1a. In March 1999, a CT scan reveals a retroperitoneal mass measuring 159.515 cm (Fig. 1a). The mass is mainly located on the left side of the abdominal aorta, extending from the left renal hilum to the aortic bifurcation. The left ureter is involved, resulting in left hydronephrosis.

Fig. 1b. After the second course of chemotherapy, the tumor was reduced in size to be 7×4.5×8 cm on CT.

Fig. 1c. In June 1999, the largest diameter of the mass was reduced from 15 cm to 8 cm on CT.

Fig. 1d. In April 2000, the tumor was reduced to 4 cm in diameter.

Fig. 1e. On January 23, 2001, the mass seems to have become scar tissue containing calcification without any viable tumor cells on CT. Thereafter, the tumor-like lesion was virtually undetectable on CT.

Fig.1f. On October 19, 2009, the tumor was undetectable on CT.

Fig. 2. Correlation of treatment with the changes of tumor size and 1CTP.

Fig. 3a. These are numerous pulmonary metastases, including 3 major lesions (June 12, 1996 ).

Fig. 3b-1 and 3b-2. After the start of IL-X treatment, some of the lung metastases regressed and the number of pulmonary lesions showed a decrease on CT (January 31, 1997).

Fig. 4a. The main abdominal aortic lymph node metastasis is 2.8 cm in diameter (June 12,1996 )

Fig. 4b. The main abdominal aortic lymph node metastasis has decreased in size by 70% on CT (February 3, 1997).

Fig. 3c. At 3.6 years after the start of treatment (January 7, 2000), the three large metastases in the lungs have regressed significantly, but many small metastases still remain scattered throughout the lungs.

Fig. 4c. The main abdominal aortic lymph node metastasis has decreased in size on CT (January 7, 2000).

Fig. 3d-1 and 3d-2. All of the metastases in the lungs have disappeared on CT (May 7,2005) .

Fig.3e-1 and 3e-2. No lung tumors are detected by CT on September 2, 2009.

Fig. 4d. All of the abdominal aortic lymph node metastasis have disappeared on CT (May 7, 2005).

Fig.4e. No abdominal aortic lymph node metastases are detected by CT on September 2, 2009.

Fig. 5a. The IFN-γ level showed a decrease from 91.6 IU/ml (March 6, 2001) to 27.6 IU/ml (June 21, 2004), except for slightly increased levels of 60.8 IU/ml and 53.0 IU/ml on February 4, 2002 and June 10, 2003, respectively. The IFN-γ level (IU/ml) showed a linear correlation with the duration of fungal extract treatment (days) during the period from September 16, 1999 to December 12, 2000. This relationship was also confirmed during the period from March 6, 2001 to June 21, 2004, when there was no evidence of tumor on CT. Fig. 5b. Changes of the IL-12 level during treatment. From September 16, 1999 to December 12, 2000, the IL-12 level increased as the treatment period was prolonged. From March 6, 2001 to June 21, 2004, when no tumor was detectable on CT, the IL-12 level was negatively correlated with the duration of treatment.

Fig. 6a. Measurement of IFN-γ was possible from April 23, 1998. The IFN-γ level was 55.8 IU/ml on day 1, and it increased to 134 IU/ml on March 3, 2000 and to 178 IU/ml (maximum) on September 1, 2000, showing a correlation with the duration of treatment. After this, the two metastatic lesions decreased markedly in size. The IFN-γ level started to decrease from September 1, 2001 and fell to 22.3 IU/ml on March 12, 2005. An inverse correlation between the IFN-g level and the duration of treatment was observed during this period.

Fig. 6b. The IL-12 level increased slightly as the treatment period was prolonged from April 23, 1998 to March 3, 2000. Tumor masses in the lungs and abdominal aortic lymph nodes showed significant regression by January 7, 2000. During the period from September 1, 2000 to March 12, 2005, all of the tumor masses initially detected on CT disappeared, and the IL-12 level showed an inverse correlation with the duration of treatment.

References

1) Nakazato H, Koike A, Saji S, Ogawa N and Sakamoto J. Efficacy of immunotherapy as adjuvant treatment after curative resection of gastric cancer. Study Group of Immunochemotherapy with PSK for Gastric Cancer. Lancet. 343(8906):1122-6, 1994

2) Methods for measurements of IFN-γ, and IL-12 production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) stimulated with phytohemagglutinin (PHA).

A) Separation of PBMCs

Heparinized peripheral blood is mixed with the same volume of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The mixture is layered over Conray-ficoll solution (density 1.077) and centrifuged for 20 m at 400 G. After plasma is discarded, the layer containing PBMCs is collected, mixed well with PBS, and centrifuged for 5 m at 400 G. Then the layer containing PBMCs is collected again. This process is repeated twice. The PBMCs thus obtained are added to RPMI-1640 medium (medium) containing 10% fetal bovine serum and lymphocytes are counted. Then the lymphocytes are adjusted to 1106 cells/ml by adding medium as required (adjusted PBMCs).

B) Culture of PBMCs

A 200-l aliquot of adjusted PBMCs is mixed with 20 l of PHA (20 g/ml; Difco Co. Ltd.), and the mixture is pipetted into a 96-hole microplate. Then the PBMCs are cultured for 24 h under 5% CO2 at 37C after which the supernatant is harvested and assayed for IFN-γ and IL-12.

C) Measurement of IFN-γ and IL-12

(1) IFN-γ assay: Culture supernatant is added to an ELISA microtiter plate (Biosource Europe S.A.) coated with anti-human IFN-γ monoclonal antibody, the plate is washed, and peroxidase labeled anti-human IFN-γ monoclonal antibody is added to the plate. After washing the plate again, the substrate (TMB) is added. Then the IFN-γ titer is measured from the absorbance at a wavelength of 450 nm by an Emax plate reader (Molecular Devices) with reference to the standard curve.

(2) IL-12: The same procedure is carried out for measurement of the IL-12 titer in culture supernatant, employing an ELISA microtiter plate coated with anti-human IL-12 monoclonal antibody (Biosource Europe S.A.) and an Emax plate reader (Molecular Devices).

3) Fabre E, Jira H, Izard V, et al. ‘Burned-out’ primary testicular cancer. BJU Inter 94:74-78, 2004

4) Kato M, Ikeda Y, Namiki S, et al. Spontaneous regression of pulmonary metastases from testicular embryonal carcinoma. Inter J Urol 15:265-266, 2008

5) Sarid DL, Ron IG, Avinoach I, et al. Spontaneous regression of retroperitoneal metastases from a primary pure anaplastic seminoma. Am J Clin Oncol 25(4):380-382, 2002

6) Cole WH Efforts to explain spontaneous regression of cancer. J Surg Oncol 17(3):201-9, 1981

7) Papac RJ Spontaneous regression of cancer: possible mechanisms. In Vivo 12(6):571-8, 1998

8) Stephenson HE, Deelmez JA, Renden DI, et al. Host immunity and spontaneous regression of cancer evaluated by computerized data reduction study. Surg Gynecol Obstet 133:649-55, 1971

9) Saleh F, et al. Direct evidence on the immune-mediated spontaneous regression of human cancer: an incentive for pharmaceutical companies to develop a novel anti-cancer vaccine. Curr Pharm Des 11(27):3531-43, 2005

10) Droller MJ Biologic response modifiers in genitourinary neoplasia. Cancer 60:635-644, 1987

Copyright(C) 2006-2019 Orient mitaka clinic All Rights Reserved.